PERF has labeled these materials the ICAT Training Guide (as opposed to a “lesson plan” or “curriculum”) for a reason. The materials provide a new approach to incidents that in the past have sometimes ended with a use of force by police. In many cases, the incidents could potentially have been resolved peacefully if officers had better options for assessing the situation and using specialized communications skills and tactics to “slow the situation down,” while protecting their own safety and public safety.

Because some police agencies and training academies already have curricula on topics such as crisis intervention, communications, tactics, and decision-making, it may not be possible to simply drop the ICAT Training Guide into an existing training program. Elements of this Training Guide may duplicate certain aspects of a police department’s current training. In other cases, parts of this Training Guide may contradict existing policy or training. Thus, each agency should review the six Modules of this Training Guide, and decide how to merge new concepts with existing training, or to make adjustments as necessary.

And although the lessons in the ICAT Training Guide are especially pertinent to critical incidents involving subjects who are not armed with a firearm, some of the concepts, approaches, and techniques presented here can also be applied to certain situations in which firearms may be present. For example, if a barricaded subject has a firearm but is not actively shooting or pointing the weapon at an officer or someone else, many of the elements covered in this Training Guide—good decision-making, effective communications, officer safety approaches, and sound tactics—are still critical parts of a safe and effective response.

This Training Guide will be most effective in agencies and training academies that have reviewed and embraced the 30 guiding principles on use-of-force policy, training and tactics, equipment, and information exchange that are contained in PERF’s 2016 report, Guiding Principles on Use of Force. That 127- page document provides the context, supporting research, and commentary by leading police executives and other experts about how the guiding principles and this Training Guide were developed and how the two documents complement each other.

ICAT Is Flexible and Adaptable

PERF encourages police agencies and training academies to be creative in how they choose to use the ICAT Training Guide and to do so in ways that best support their own training needs. Some agencies and academies may decide to present the Training Guide materials as a stand-alone training program for the types of situations in which patrol officers encounter a person behaving erratically, possibly because of a behavioral crisis, who is either unarmed or armed with a weapon other than a firearm.

Other agencies or academies may choose to incorporate the modules in this Training Guide into existing training programs on de-escalation, tactical communications, or crisis intervention. Still others may want to take elements of individual modules and create their own lesson plans. The ICAT Training Guide is designed to accommodate these and other approaches.

ICAT can be used to support recruit training, in-service training, or both. Again, it will be up to individual agencies and academies to determine how to best integrate this material into their overall training strategies and approaches.

One of the key points raised by the training experts that PERF consulted in the development of this Training Guide is that many skills—in particular, tactical communications skills—are perishable and need to be reinforced and practiced on a regular basis. This guide can be used to provide officers with regular “training booster shots” in a number of areas—for example, patrol supervisors could use a video case study approach with their officers to keep skills up to date. Elements of this training can also be reinforced during roll call or team training exercises.

The ICAT Training Guide is presented in six modules:

Module 1: Introduction. This module explains the purpose and focus of the training, emphasizing that public safety

and officer safety lie at the heart of the entire Training Guide.

Module 2: Critical Decision-Making Model (CDM). This module discusses the importance of critical thinking and

decision-making for officers responding to the types of incidents that are the focus of ICAT. It presents the Critical

Decision-Making Model as a training and operational tool for agencies to structure and support officers’

decision-making.

Module 3: Crisis Recognition and Response. This module provides basic information on how to recognize individuals

who are experiencing a behavioral crisis caused by mental illness, drug addiction, or other conditions. It also provides

techniques on how to approach such individuals, initiate communications, and try to stabilize the situation.

Module 4: Tactical Communications. This module provides more specific and detailed instruction on communicating

with subjects who are agitated and initially non-compliant. It focuses on key communications skills, including active

listening and non-verbal communication, that are designed to help officers manage these situations and gain voluntary

compliance.

Module 5: Operational Safety Tactics. Using the Critical Decision-Making Model as the foundation, this module

reviews critical pre-response, response, and post-response tactics to incidents in which a person in behavioral crisis

is acting erratically or dangerously but is not brandishing a firearm. It emphasizes concepts such as the “tactical

pause” to begin developing a working strategy; using distance and cover to create time; using time to continue

communications, create options, and bring additional resources to the scene; tactical positioning and re-positioning;

and teamwork.

Module 6: Integration and Practice. This module pulls the preceding modules together. Using scenario-based exercises and

video case studies, it gives officers additional opportunities to practice the concepts and skills learned throughout the

training.

These modules, and the material within each module, are presented in a recommended sequence. However, it is not

required that the material be delivered in this exact order or format. An agency or instructor may feel it beneficial

to transition between modules to more closely represent recent events or challenges particular to the operational

environment for that agency.

Different Training Methods for Visual, Auditory and Kinesthetic Learners

ICAT utilizes both lecture/discussion-based training and practical instruction. As such, the guide attempts to

accommodate the three basic types of adult learners: visual, auditory, and kinesthetic.

Because traditional, lecture-based classes do not provide kinesthetic learners with an avenue to easily retain the

information presented, the guide includes multiple hands-on activities. In addition, some individuals do not have a

single learning style. For example, visual/kinesthetic learners will retain more information if it is presented across

the two different learning styles. The Training Guide is designed for these types of learners as well.

The material is presented in a basic lesson plan format that should be familiar to police trainers. It is also designed

for agencies and academies to customize the modules to match their own policy considerations, training philosophies,

state-level requirements, and available training resources.

Training Goals, Objective and Approaches

For each module, the Training Guide presents course goals and learning objectives. The guide also provides suggestions

about the amount of time that should be devoted to each module, based on the material presented and recommended

exercises. However, individual agencies or academies can adjust the material and the amount of time used to cover it.

Lectures and discussions: Each module includes an outline of suggested material to cover during lectures and class

discussions. This material is not tightly scripted; rather, individual instructors will be expected to provide additional

context and depth to the major learning points that are included. To assist instructors, the guide includes

“Instructor Notes” that provide additional explanation and resources. Again, agencies and academies should add to

these notes as appropriate.

Suggested Power Point: To support the lectures and class discussions, the Training Guide includes a Power Point

presentation for each module. Use of the Power Point files is recommended, but optional. Agencies and academies

should customize the presentations to fit their training requirements and philosophies. The format of the Power Point

slides is simple, allowing agencies or academies to insert their own logos or other training information and visuals,

as appropriate.

Video case studies: The Training Guide includes several video case studies that illustrate and amplify the material

presented in the various modules. The modules include suggested questions and discussion points for each video

case study. Instructors should feel free to augment these discussion points or introduce different or additional videos

that cover the same learning objectives as those included in the Training Guide.

Scenario-Based Training (SBT): The Training Guide also includes several scenario-based training exercises. These

exercises are presented in two ways: as written scripts and, in some cases, as videos of the recommended scenarios.

The scripts are intended to help agencies and academies create and run their own SBT exercises. They provide the

background on the scenario and guidance to the role players, as well as key discussion and learning points for the

instructors to use. The SBT videos can be used in one of two ways. For agencies and academies that want to run their

own live SBT exercises, the videos offer a visual guide in how to structure and stage the exercises. For agencies and

academies that may not be able to run their own SBT exercises, the videos can be used as case studies to illustrate the

same discussion points and learning objectives. It should be noted, however, that to most effectively reach different

types of adult learners, running actual scenarios is recommended.

Some Tips and Techniques for Conducting Scenario-Based Training

Consider Stepping Outside the Regular Training Academy Structure

The training experts who advised PERF on the ICAT Training Guide emphasized that selecting the right instructors to

deliver this type of training is critically important. Some agencies that have rolled out new use-of-force training have

decided to go outside their traditional academy structure, and use trusted and respected individuals within their

agencies, as well as community leaders or outside experts in some cases. When training challenges conventional

thinking and presents innovative new ideas and approaches, it is essential to have trainers who endorse the new

approach and who are viewed as leaders within the organization.

That is the blueprint the Camden County, NJ Police Department followed in rolling out its “Ethical Protector” training—

a department-wide initiative that stresses de-escalation, tactical communications, and the sanctity of human life. Rather

than assigning the new training to regular training academy personnel, the department identified and recruited

approximately 20 informal leaders within the agency. These were people who, regardless of rank, assignment, or

patterns of experience, were well known and widely respected by fellow officers. The department provided those

personnel with intensive train-the-trainer instruction on the Ethical Protector philosophy and program. These mentors

then delivered the Ethical Protector training to the entire department. Department leaders and rank-and-file officers

have attributed the effectiveness of the training to this unconventional approach.

The chief must endorse the training—publicly and internally: Experts said it is critically important for the police

chief, sheriff, or other agency top executive to proactively demonstrate support for the training with internal and

external audiences. That is why Module 1: Introduction recommends an in-person visit or video message from the

agency’s chief executive at the very beginning of the program. Beyond just endorsing the training, chief executives

and other top leadership can demonstrate their support by either attending the training themselves or spending time

getting an overview of the training. In addition, it is important for all instructors to enhance and localize the training

using anecdotes and experiences from their community.

Involve community partners: Agencies should also look to include other community partners in the training, where

appropriate. For example, the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) is closely involved in the Crisis Intervention

Team (CIT) training offered in many agencies. The ICAT Training Guide recommends that NAMI’s

“In Our Own Voice” program could be easily and effectively integrated into Module 3: Crisis Recognition and Response.

Other community partners in fields such as mental health, substance abuse, juvenile justice, elder care, and caring for

other vulnerable populations could be effectively incorporated into the ICAT Training Guide as well. These partners add

not only subject matter expertise, but also legitimacy to the training. In the interest of transparency and building

community-police relations, agencies should also consider inviting selected community stakeholders, and possibly the

news media, to observe the training in action.

Assessment and Testing Protocols

Each agency and academy will need to determine how to present ICAT within the context of its own assessment and

testing protocols. This Training Guide does not include recommended or sample examinations or other assessments.

These types of protocols are important in demonstrating that officers have understood and can implement the key ideas

presented in the Training Guide. Developing these instruments will be up to the individual agencies, based on their own

experiences and preferences.

Some Tips and Techniques for Conducting Scenario-Based Training

The training experts who have assisted PERF in the development of the ICAT Training Guide emphasized the importance

of scenario-based training (SBT) for police officers. They said SBT is particularly important for the subject of this training:

patrol officers responding to an agitated subject, possibly in crisis, and either unarmed or possessing a weapon other

than a firearm. These situations are dynamic, potentially dangerous, and require a mix of communications, tactical, and

decision-making skills. SBT provides opportunities for officers to practice and demonstrate proficiency in all of those

skills sets, in a realistic, hands-on, and sometimes stressful environment.

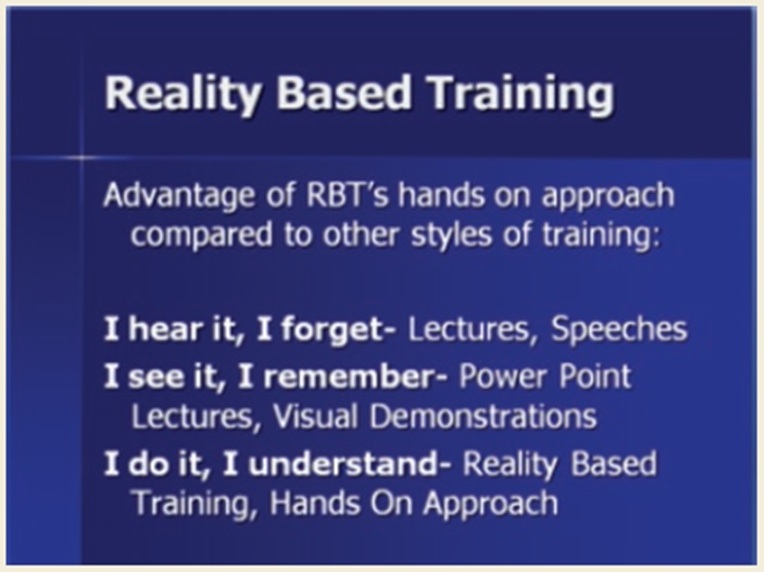

What is scenario-based training? (Also referred to as reality-based training, or RBT)

The Dallas Police Department, which helped to pioneer the concept with the creation of a dedicated Reality Based

Training Team in 2006, provides this definition:

Reality Based Training is training that places the student into a setting that simulates a real-life encounter, in order

to test his/her ability to respond to an incident while acting within the law and departmental policy. RBT allows a

student to experience various situations under stress before they reach the street and experience them for real.

The student can experience these situations while in a safe/sterile environment.

Scenario-based training is designed to complement, reinforce, and extend the other training methods that are used

here and in other training. The Dallas Police Department presents the following learning continuum, emphasizing the

advantages of RBT, or SBT:

Building officers’ skills and confidence

Training experts emphasize that while effective SBT exercises inject physical and mental stress into the scenarios, SBT is

ultimately designed to build up officers’ skills and confidence. Scenarios should be designed for officers to practice and

learn—and to succeed. SBT is not effective if the scenarios are seen as “gotcha” exercises that embarrass or shame

students for not performing perfectly every time. The training should emphasize that the situations are complex and difficult

to navigate until they have been practiced and the critical thinking process starts to become more automatic. The

scenarios included in this. Training Guide adhere to these principles, and it is important for agencies and academies

to conduct their SBT in this same spirit.

How to select and coach role-players?

A key component of any successful SBT exercise is the selection and coaching of “role players.” Role players are the

people who portray, for example, the subjects who are acting irrationally, relatives who call the police and may help

calm the person down, and bystanders who may interfere and complicate the police response.

Role players must not only understand the parts they are playing; they must immerse themselves in those roles.

The training experts who advised PERF emphasized that for SBT to be effective, the role players must be realistic and

adept at playing their parts. Police department staff members can be effective role players, but they must demonstrate

the ability to carry out the parts in the scenarios. However, it is not recommended that police personnel attending the

training also serve as role players during that same training session. The roles of students and role players should be

kept separate. Some agencies and academies hire professional actors, where resources are available. Others, including

the Metropolitan Police Department of Washington, DC, partner with the theater programs at local colleges or

universities to supply student actors at little or no cost.

Two basic approaches to running scenarios

PERF’s training experts identified two basic approaches for running SBT exercises:

- Stop the exercise at key points to discuss what is happening and various possible responses, or

- Run through the entire exercise, and then discuss.

Under option 1, instructors stop the action at key points during the scenario, sometimes to reinforce a successful action

or technique by the officer, to point out warning signs, or to amplify an important teaching point. Frequent “cuts” in the

action are not intended to indicate that anything is necessarily “wrong.” Rather, they represent key decision points at

which to explore tactical options (e.g., Where is your cover? What are your options for protecting yourself? Has the

nature or severity of any threat posed by the subject changed? How has the threat changed? Is the person becoming

more or less compliant? What communications and tactical strategies are warranted given the change in the threat?).

Instructors should emphasize these points prior to the scenario starting, so that students understand the purpose

behind the frequent breaks in the action.

One other consideration: when conducting this type of training, part of the memory has no recall of the perception of

time. By infusing “pauses” into the scenario, the student has more time to come up with the correct answer or action.

When recalling the scenario later, the student will likely recall only his or her correct actions, not the pauses. This

allows for the student to perform the “perfect rep,” which will later be recalled as a template when confronted with a

similar scenario, either in training or in the field.

The New York City and St. Paul Police Departments are among the agencies that use this stop-and-discuss approach.

The primary advantage is that issues and questions can be addressed right away as they come up. The main

disadvantage is that the “cuts” interrupt the flow of the scenario, and thus do not mirror actual events as they

would unfold.

Under option 2, instructors allow the scenario to run all the way through, and then debrief and discuss important

learning points. Prince William County, VA and Police Scotland, among others, have adopted this approach. The

primary advantage here is that the scenarios more realistically mimic the structure and pace of the actual

situations that officers will encounter on the street. A potential disadvantage is that some key decision points may

not be fully covered in the post-scenario discussion and debrief.

Neither approach is necessarily better than the other. Each has its strengths and drawbacks, and agencies and

academies will need to decide which approach works better for them. Agencies may use a mix of options 1 and 2,

depending on which works best in a given scenario. In a certain scenario, it may make sense to stop just once to

highlight a critically important decision point, but otherwise allow the scenario to run without interruption.

In all scenarios, the purpose is not to render a simple “pass-fail” judgment on individual officers. Rather, SBT is

intended to getofficers to think about their decision-making, both as the situation unfolds and after the fact, as the

officers are called on to explain their actions.

Finally, some agencies, including Oakland and Fresno, CA, take their scenarios all the way through to the end of

the call for the officer. For example, officers are expected to call for medical backup if appropriate, write reports, and

conduct other follow-up activities, as they would in a real-world encounter.

What to do with students not actively engaged in an SBT exercise?

One of the common concerns about SBT is that there is a lot of “down time” for students who are not actively involved

in the scenario. The training experts who advised PERF generally recommended that students who had not yet been

through the scenario should not be allowed to observe it before their turn. After students have completed the scenario,

some agencies allow them to observe subsequent scenarios. In some cases, students are given specific “assignments,”

such as watching for particular communications techniques or tactical approaches. However, students should never be

involved in evaluating or debriefing with other students; those are the job of the instructors.

One other option (recommended in this Training Guide) is to split a class into two groups (or more, depending on the

overall size of the class). While one group is performing SBT, the others can be engaged in other practical training

activities, such as video case studies.

What type of investment do agencies and academies need to make in SBT?

The training experts who advised PERF on ICAT emphasized that agencies and police academies need to be prepared to

invest in their scenario-based training. This investment means devoting resources to create and implement a robust SBT

program, with realistic scenarios, high-quality role players, and highly trained instructors. Agencies should also consider

investing in video recording and editing equipment to film and play back scenarios for students. Such videos can be useful

during one-on-one discussions about an officer’s actions during the scenario.

Realistic scenes: Agencies and academies should work to provide realistic locations for scenario-based training. Some

organizations have robust “tactical villages” and similar facilities to stage a wide range of scenarios. Other agencies may

need to be creative in finding realistic locations, such as storefronts that are temporarily closed, vacant office space,

school facilities after hours, and the like.

Don’t rush the scenarios: Devoting time to scenario-based training also means giving individual scenarios the time to

play out. One of the key lessons of the PERF Guiding Principles on Use of Force is that police often achieve better

outcomes if they can “slow a situation down,” in order to give themselves more time to communicate with the subject

and establish a rapport, assess the nature of the crisis, thoughtfully consider options for responding, call mental health

experts and additional police resources to the scene, and give the person time to calm down and de-escalate. Thus,

patience is important in handling these incidents.

It is equally important to have patience and allow time for the scenarios in this training to play out. By giving scenarios

the time to evolve and play out, agencies and academies send the message to officers that their goal is to resolve the

situation peacefully, which often does not mean quickly, and that officers are encouraged to take the time they need.

It is important to emphasize this point, because in many departments, the traditional way of thinking is that officers

should resolve every incident as quickly as possible, so the officers can move on to the next call.

Train as a team, if possible: Whenever practical, agencies and academies should attempt to have units, or at least

partners, go through scenario-based training as a team. This approach allows for units and partners to practice team

tactics during SBT, which is likely to translate into greater coordination and increased officer and public safety in

the field.

|