|

April 19, 2025 Former Washington Post publisher Don Graham on Watergate, the Unabomber, and his 18 months as a police officer

PERF members, Jerry Wilson, who served as chief of the Washington (D.C.) Metropolitan Police Department (MPD) from 1969 to 1974, died last month. He was an impressive police chief who was years ahead of his time in reforming the department. Shortly after Chief Wilson passed away, former Washington Post publisher Don Graham wrote an op-ed for the Post praising Wilson’s exceptional leadership. Graham was writing from a unique perspective. The son of former Washington Post publishers Katharine and Philip Graham, Don graduated from Harvard University in 1966, served in the U.S. Army in Vietnam, worked as a D.C. police officer for a year and a half, then joined the family business at the Post, serving as the paper’s publisher from 1979 to 2000. His time as a rookie officer came during Jerry Wilson’s tenure as police chief, so he had firsthand experience with Chief Wilson’s leadership. I reached out to Don, who graciously spoke to me for an hour about his experiences with the MPD, the role of police reporters in breaking the Watergate story, his interactions with the FBI during the Unabomber attacks, and his thoughts on how police chiefs and reporters might find common ground.

Don Graham. Source: C-SPAN Chuck Wexler: What was attending Harvard like in the 1960s? Don Graham: It was a fascinating time. I enrolled in a very different Harvard in 1962. When I applied, I had a one-in-three chance of getting in. Now I would have a three percent chance of getting in. Everybody from my day says, “I’d never get in now.” I was coming not only from Washington, D.C., but a very unusual background in Washington, D.C. I’d sat at my mother and father’s dinner table all my life and had met a lot of newspaper people and a few people in government. I met more after John Kennedy became president, because my father had known him a little and knew Lyndon Johnson, the vice president, better. [My father] was interested in the people working for Kennedy, so I had listened to a couple of them a bit. I went to Harvard in ’62, and the Cuban Missile Crisis was in November of that year. To anybody my age, those words are scary. We all wondered if we were going to die the next day. By the time I graduated in 1966, Kennedy had been assassinated and Johnson was president. Starting in 1965, when Lyndon Johnson sent the first couple divisions of American soldiers into Vietnam, there was no political subject at Harvard except Vietnam. We kept sending more troops, and I understand Harvard became quite a different place by 1968 and 1969. But I was no longer there. Wexler: And after graduating you served in Vietnam. Graham: I graduated from Harvard in June of 1966 and technically I volunteered for the draft, which simply meant I said, “I’m here, you’re going to draft me sometime, so go ahead and draft me.” Because otherwise I could have waited for months. I could have gone on to graduate school and thereby extended my student deferment, but I never had the least desire to go to any grad school. My dad had been in World War II, and my mother and father were very old-fashioned patriotic Americans. And I felt that way too. I did not love the idea of the war in Vietnam, even in 1966. But I didn’t feel like saying, “Therefore I’m going to go become a lawyer,” or something. So I volunteered for the draft. I did not ask them to send me to Vietnam, but I knew that was pretty likely. And they did indeed send me to Vietnam in July ’67 as a photographer and reporter. Out job was to go out in the field as much as we could, take pictures, and write stories about infantrymen and what they were doing. Only the Army ever saw any aesthetic ability in me, so they gave me a camera. Wexler: When you returned from Vietnam, you joined the Metropolitan Police Department in Washington, D.C. How did your family feel about that? Graham: My father died in 1963, when I was 18. My mother was brave enough, with her four children cheering loudly, to say that she was going to run the Post and the Post Company. No woman was then running a company of that size, and that was a fabulous decision she made. I was discharged from the Army in July 1968, and in April 1968 there had been a three-day riot in Washington, D.C., after Martin Luther King was shot. I wasn’t there, but people rioted, as they did in many American cities. I read about the riot in Washington and I knew my mother wanted me to come work at the Washington Post, but I told her, “I think I would be more use to you if I did something first to learn about the city.” My first thought was that maybe I should go teach in a D.C. public school, but at that time you had to have an education degree to teach in a public school, and I did not. The police at that time were really desperate for people. The patrol side of every police department, which is most of every department, was all male. The draft was on, so the government was gobbling up a whole lot of 18- to 19-year-olds before they could even consider becoming cops. I wasn’t going to stay there forever. My mother told me she would prefer I came to the Post, and my then-wife was going to graduate from law school a year and a half later. I told the sergeant recruiting me that I would stay only a year and a half, and he said “that will be above average.” D.C. had the lowest-paying department in the metropolitan area. We’re surrounded by departments in Maryland and Virginia. There’s also the [U.S.] Capitol Police and the [U.S.] Park Police. All of those paid more than D.C., so it was very common for D.C. police to serve for a year or two then go for a better job. Wexler: You recently wrote a Washington Post op-ed about Jerry Wilson, who was chief of the Metropolitan Police Department while you were an officer and passed away last month. Why was he such a great leader in your mind? Graham: In the year and a half I was on the department, I never met Chief Wilson. But by the time I left, I was so impressed with the guy and became more impressed after that. As a reporter I met him and got to know him a little bit. He understood something that’s very hard to understand, which is how to make decisions and then get people in the first-level job, the line police officers, to react in the way he wanted them to. A prime example was while I was in the academy. All of us understood that there had been the riot in April 1968, and then there had been a persistent series of police-community interactions that were really bad from a public relations point of view and could have led to more rioting but didn’t. The police wound up shooting and killing a man in an episode that started in a dispute over a jaywalking ticket. They went to the house of a woman whose family had called because she was having a mental disturbance and yelling at and threatening them. The woman was on the porch of her house with a small kitchen knife, and they wound up shooting her. So this was very much on the minds of everybody in Washington. In week four when we were in the academy, the sergeant in charge of our education said our schedule was going to change on Friday. He said, “You have already studied the general order about when a police officer in Washington, D.C., can shoot at someone. We are going to take an hour to read that order again and I’m going to ask for all your questions about what that order means and how the department wants you to act in certain situations.” And the same thing was going on in every roll call across the city. The chief and the higher-ups were sending a message that using your weapon is a big thing for a police officer to do, and if you do it, you better do it in line with the regulation. And we did that every Friday. The conclusion I drew was that if I were to use this service weapon not in compliance with somebody’s order, the department may not stand behind me. Whereas if I use it properly, in defense of my own life or to save somebody else’s life, the department will stand behind me. I won’t claim I got it the first week, but I certainly got it the second week.

D.C. Police Chief John B. Layton, left, and then-Assistant Chief Jerry Wilson on April 4, 1968, the first night of rioting that followed the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. (Ray Lustig/The Washington Star) Wexler: Your op-ed also noted that Chief Wilson hired many more Black officers and hired female officers to work on patrol. Graham: When Chief Wilson took over, a very odd thing happened in Washington, D.C., that couldn’t have happened in any other place. This was a time before there was an elected local government in Washington, so the mayor, Walter Washington, had been appointed to his job by the President of the United States, Lyndon Johnson. Presidents took quite an interest in the affairs of Washington, D.C., because they didn’t want to be blamed if something went wrong. Lyndon Johnson, having seen the riot in 1968, did not want to be blamed if he was running for reelection and crime in Washington was going up. So he added a thousand officers to the D.C. police department. But he didn’t run for reelection, and Richard Nixon was elected. Nixon came in and had the same concern, so he added another thousand officers to the D.C. police department. So they went from having an authorized strength of 3,100 and a real strength of 2,600 to an authorized strength of 5,100. They had a hiring binge, and Chief Wilson was smart enough to say that one of the problems was that the department was 18 percent Black in a city that was 72 percent Black. The department was overwhelmingly White, and that was resented. He put two very able people in charge of hiring and instructed those people, among other things, to hire the ablest people they could, but to look for as many potential Black officers as they could find. By the early 1970s, I think the department went from 18 percent Black to 43 percent Black. That was possible because of the huge increase in head count. Sometime after I left the department, the war in Vietnam was still on, and it was harder and harder to find young men to join the all-male patrol force. There were no women on patrol systematically in any big city police department in the United States. Jerry got the Police Foundation to test the outcomes if he hired 100 women and put them on patrol compared to 100 men being hired at the same time. Of course it came out they were the same or, maybe on average, a tiny bit better. To supervise them, he turned to Private Mary Ellen Abrecht, an amazing young woman who later became a lawyer, a prosecutor in the U.S. Attorney’s Office, and a Superior Court judge. Wexler: You then left the Metropolitan Police Department and joined the Washington Post. Shortly after you joined, the Watergate scandal happened. Tell me about that from your perspective. Graham: I was hired as a reporter in January 1971, and I jokingly say I was hoping to at least be the best reporter hired in 1971. But later that year we hired Bob Woodward, and Woodward is still the best reporter in Washington. In July 1972, the Watergate burglary took place. I was no longer in the newsroom; I was working in other departments around the paper. From July ’72 to August ’74, Woodward and [Carl] Bernstein were ceaselessly working on it. They were interviewing everybody and trying to advance the story one more click. That became the most important story the Washington Post ever reported.

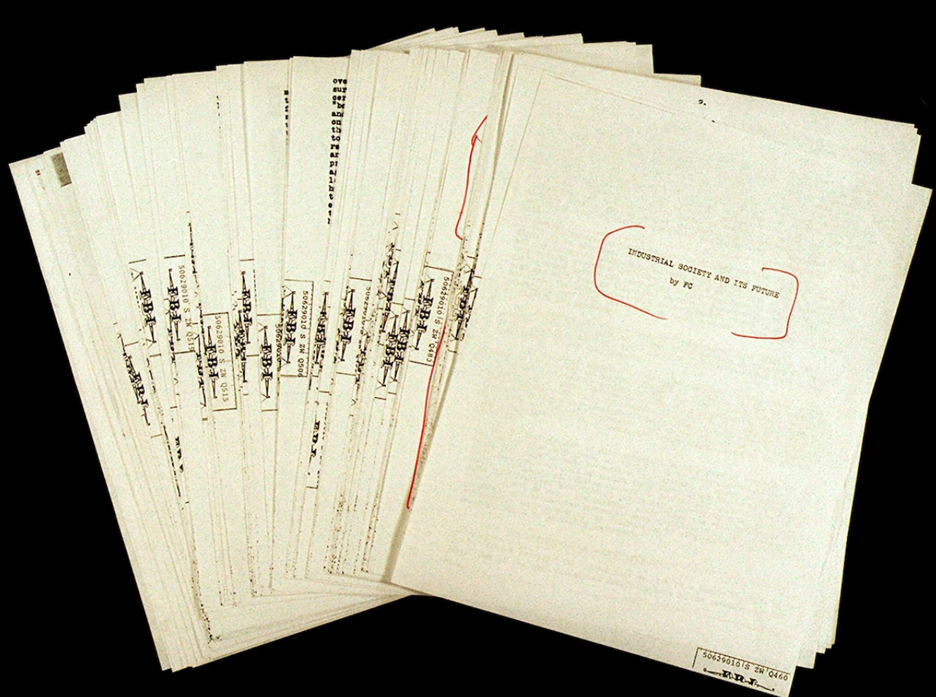

The initial report of the Watergate break-in as it appeared on the front page of the June 18, 1972, edition of the Washington Post. Source: Washington Post Wexler: How did police reporters help break the Watergate story? Graham: The Post had a day police reporter named Al Lewis who had been on the paper for 50 years and a night police reporter named Gene Bachinski who had been on the paper for 20 years. They both were well-known to the cops. Cops respected them, and they respected the cops. When the Watergate burglary took place, Gene Bachinski asked one of the officers who made the arrests, “Do you have any information on who these characters are?” He gave Gene a look at the address book of James McCord, one of the Watergate burglars. That address book had an entry that said “H Hunt. WH” and a number that started with “456,” which everyone knew was the White House. Gene gave that information to Woodward and Bernstein. Bernstein called that number and asked to speak to Mr. Hunt. His secretary said, “He’s down the hall in Mr. Colson’s office”—Chuck Colson was the toughest aide to Nixon—“and I’ll get him for you.” Hunt came on the phone and Bernstein said, “Mr. Hunt, this is Carl Bernstein at the Washington Post. Why was your name in the address book of one of the burglars arrested in the Watergate burglary?” Hunt said, “Oh s***,” and hung up the phone. Police reporting, by Gene Bachinski in that case and Al Lewis in other cases, was very important to the reporting of the Watergate story. Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein would still tell you that. Wexler: Moving forward to 1995, tell me about the “Unabomber” incident from your perspective. Graham: Some time in 1995 I got a call from a man named Bob Bucknam, who was the chief of staff to Louis Freeh, the head of the FBI. He said, “If you look in your mailroom, we think there is a brown paper envelope addressed to someone at the Post that contains a letter from the Unabomber.” The Unabomber was a terrorist who went to great pains to keep himself anonymous while he mailed bombs to people he disliked for some reason. He thought that we should abolish technology, so he maimed a professor of computer science at Yale. He killed three people and tried to kill many others. People were terrified of this guy because his bombings were so random. So Bob Bucknam said to me, “Would you mind giving us this document before your people read it so that we can check for fingerprints?” He said, “There’s almost no chance there are any fingerprints, but we really ought to check.” Speaking for the Washington Post, I told him we wouldn’t mind in the least. Ordinarily we don’t share information about sources with the FBI, but we’re not going to treat this terrorist as a source. This is a mass murderer; we’re certainly not in the line of protecting him. So one of our editors went with the document, the FBI checked it over, and they brought it back. The document said, “I have written a long essay about my political philosophy and I want it printed in either the Washington Post or New York Times or published as a book in the next 90 days. If that happens, I will not send any more bombs through the mail. But if you don’t do it, I will send at least one more bomb through the mail aimed to kill.” Then I called the publisher of the New York Times, who was a friend of mine, Arthur Sulzberger. We knew each other quite well and trusted each other, and that was important, because we both immediately said, “Let’s do this together. We cannot let this man play our two newspapers off against each other, so let’s do this in lockstep.” So we did. The first thing we did was give the so-called manifesto to each of our editors. They both read it and said, “No, there’s no way we would print this.” So then I said to Arthur, “What do you say we go to the FBI and tell them that we’re not necessarily going to do what they advise us, because we’re the Washington Post and the New York Times and we don’t generally do what they advise us. But our editors have told us there’s no journalistic interest in printing this, but there may be a public safety reason for printing it. If this is indeed the Unabomber and your people think there’s a chance that by printing it we could keep him from sending another bomb, we don’t want to be a party to killing people. But we also don’t want to set a precedent of other people trying to do the same thing.” Arthur said, “Yes, let’s do that.” So we called Louis Freeh on the phone and he said, “Okay, we have 90 days, and we’ll give you our advice well before day 90 so you can decide what you want to do.” They had three meetings with us. The first two were to tell us what they knew about the Unabomber, and a good deal of it turned out to be totally wrong. Janet Reno, the attorney general, attended the ultimate meeting. She said, “We think you ought to publish this as a book in pamphlet form and distribute it to bookstores around the country,” which was one of the things he had offered. We said, “Attorney General, we greatly respect your opinion, but we have a lot of authors. None of them think their publishers are doing an adequate job of distributing their book or publicizing it. They all hate their publishers. That’s not the relationship we want with the Unabomber.” So she said, “Okay, in that case, we think you ought to publish it in one of your papers, because we absolutely think this is from the Unabomber. Perhaps he won’t send another bomb, but it’s much more likely that someone will read it, probably a teacher, and think that’s their former student.” We took her advice and printed it in the Washington Post roughly 90 days later. There was considerable criticism of this decision by journalism school professors and others saying it set a terrible precedent. But Arthur and I were comfortable that somebody committing 20 years’ worth of bombings and murder in order to get a political philosophy published was very unlikely to occur more than once. Arthur and I would both tell you the heroes of this story were David Kaczynski and his wife Linda Patrik. They looked into the possibility that David’s brother Ted had been the Unabomber. She had a colleague who was a linguistics professor. They gave the document to that professor along with some letters from Ted Kaczynski to David asking what he thought was the likelihood that the two letters were written by the same person. David and his wife said, “We’re going to go to the FBI if the professor comes back and says it’s 25 percent likely,” and he came back and said 65 percent. So they went to the FBI and eventually he was arrested and convicted.

A copy of the Unabomber’s manuscript sent to the Washington Post. Source: Washington Post/FBI Wexler: The Washington Post won a Pulitzer Prize in 1999 for a series on use of force by the Metropolitan Police Department. Tell me about that reporting. Graham: It was a great series and had hugely positive consequences for D.C. Our investigative team learned that D.C. police were using their guns far more often than any other department in the country. By good luck, they published their remarkable series on this just as D.C. changed its chief of police to Charles Ramsey. Chief Ramsey changed the service weapon because the Post’s reporting convinced him that the weapon was unsafe. He had everybody on the force requalify with the service weapon. He did one or two other things, and the number of people killed by police went from 13 the previous year to one. And it stayed very low for several years afterward. Wexler: Do you think cops and reporters have something in common? Graham: One thing they have in common is people lie to them all the time. They’re careful about the information they’re getting. The police officer doesn’t rush to make an arrest based on the first accusation somebody makes. They have to check it out. And the reporter does not put in print the first allegation someone makes. They have to learn whether it’s the truth or not. Wexler: What advice would you give police chiefs on interacting with the media? Graham: I think police chiefs, like everybody who is constantly talking to reporters, get a pretty clear sense after a while of who they can trust and is trying to tell a truthful story. They will give your side, and they may give another side as well. A lot of people don’t like that a newspaper will give the views of your critics as well as you, but that is what newspapers are supposed to do. If you want to explain yourself to the public so people understand how you’re trying to change a police department, I’d find a reporter who is interested in those stories and whom you can trust. I would put some trust in that reporter until they show they’re not worthy of it. Newspapers are built on trust. We print stories, and we want readers to believe they’re true. Now people are more and more cynical about news, reporters, and media. But I know reporters all over the city who are working desperately to try to get stories right, and I’m sure if I lived in another city, I could say the same. If a police chief finds one of those reporters, it’s a great thing. Wexler: Is there anything else you’d like to add? Graham: I was a patrolman in Washington, D.C., for a year and a half. I was a decent, well-intentioned cop. I was not nearly as good as anybody who had been on the force three to five years and was still motivated and hard-working. There were police on the force who were so much better than I was. I don’t think I did the police any harm, and I don’t think I did the police a hell of a lot of good. But it did me an enormous amount of good. Being a cop, knowing my fellow cops, going on those calls, and learning what you learn about the city as a patrol officer, that was very, very important to me. But I want to make it clear that I am not an expert on law enforcement. I’m very grateful to Don Graham for taking the time to speak with me and share his wealth of experience with our members. He didn’t know me, but when I told him what PERF is all about, he immediately agreed to an interview. He’s led a very fascinating life and made a difference in this world. Happy Easter to those who celebrate and have a great weekend! Best, Chuck |