|

July 13, 2024 Chief Mike Sullivan discusses DOJ civil rights investigations and lessons learned in Louisville, Baltimore, and Phoenix

PERF members, For today’s column, I spoke with Phoenix Interim Chief Michael Sullivan about his experience with U.S. Department of Justice Civil Rights Division investigations and consent decrees. Chief Sullivan began his career with the Louisville Metro Police Department, where he served as deputy chief from 2015 to 2019. Chief Sullivan received PERF’s Gary Hayes Award in 2018. From 2019 to 2022, he served as deputy commissioner in the Baltimore Police Department, overseeing the Consent Decree Implementation Unit in his final year with the agency. Since 2022, he has been the interim chief of the Phoenix Police Department. Last month the U.S. Department of Justice Civil Rights Division released the findings of its investigation into the department, and the city and department are currently reviewing those findings. This week, Chief Sullivan spoke with me about the DOJ investigation in Phoenix, the consent decree in Baltimore, general lessons he’s learned about management, and how he stays enthusiastic about policing. Chuck Wexler: Few police chiefs have had as much experience with DOJ “pattern and practice” investigations and consent decrees as you’ve had. What has that experience taught you about management and accountability? Chief Michael Sullivan: At one point when I was the deputy chief in Louisville, my mayor asked me if we were performing up to standard on some policy issue. I told him that we hadn’t heard any complaints that we weren’t performing up to standard, but he said I hadn’t answered the question he asked. I realized that I had no way to be able to prove we were performing to the standard our policy said we were held to, and issues were only brought to our attention when something broke badly. When I went to Baltimore, I learned how to build systems and scorecards to identify issues and problems before they became big issues and problems. We became a self-assessing, self-correcting agency, and that’s been a mantra of mine in both Baltimore and Phoenix.

Source: Instagram Wexler: What are some specific examples of how you do that? Chief Sullivan: You have to be able to do performance audits, which is something I don’t think the profession does very well. You need to look at small samples to determine if people are performing to standard. Take procedural justice. We ask our people to perform to a certain standard. We ask them to introduce themselves, allow the person they’re interacting with to have a voice, explain their actions, and be fair and consistent in their actions. We are now blessed with body-worn cameras, which we weren’t blessed with when I started in this profession. We can pull small subsets of camera footage, do audits, and determine whether we’re hitting the mark 80 or 90 percent of the time. When we’re not hitting the mark, we can go back and coach those employees. And if we’re consistently not hitting the mark in one area, we can do training department-wide, rather than individually. We can do that with any area – procedural justice, use of force, traffic stops, etc. For each area, you can develop an evaluation rubric, then use body-worn camera footage to look at those interactions with the public and make sure your agency is performing at the standard that you expect. Before we only had written reports and citizen complaints to refer to when making a judgement. Now we have body-worn camera footage. Wexler: Can you share what you’ve learned about managing the different stages of an investigation by the Department of Justice’s Civil Rights Division? What do you do before DOJ is involved, once they open an investigation, once they announce their findings, and once your city reaches a consent decree or settlement agreement? Chief Sullivan: Before DOJ is involved, it’s about community involvement and developing advocates who can talk about the efforts you’re making to be involved in the community. The Department of Justice shows up in a couple ways, one of which is a sentinel event. But a sentinel event alone won’t necessarily be enough, unless there’s already a lot of community distrust. So community trust and connections can reduce that pressure. Once DOJ opens an investigation, you need to take the temperature of your local community and city to see where they stand. In the past, some communities haven’t cooperated with DOJ investigations. If you’re a self-assessing, self-correcting agency, I recommend that you work with them to provide information. You can make them go through the process of open records requests and digging through what’s publicly available, or you can provide information. If you’re a department that’s willing to get better and has already taken certain steps, I’d encourage you to cooperate and find a path forward.

Source: Instagram Most cities sign an agreement in principle before receiving the findings report, but we didn’t in Phoenix because we first wanted to see what was in the report. I now have a team of folks looking at the 130 incidents in the findings report. Those incidents paint a challenging picture for the city, but they don’t give us incident numbers or provide the date and time. So we have to identify those incidents and make sure we have the full context for each and every one of those situations. Because these don’t paint a good picture of the department, but I want to know the entire context. Did we make a policy change? Did we discipline the officer? We’re doing that now, and we will be putting up a dashboard that will identify those incidents and provide as much information as possible to the public. Once you have a consent decree, as we had in Baltimore, you have to look at every section of that consent decree and develop a strategic plan to come into compliance in every area. It’s a big project management challenge, and I think that’s why some cities struggle when they’re in that situation. In Phoenix, we didn’t wait for the findings report to start making changes. We brought in ICAT training to deal with situations where people are armed with something other than a firearm. If those situations are handled poorly, you can lose trust with the community. We redid our use-of-force policy. The constitutional violations usually happen in a few areas: use of force; stops, searches, and arrests; and First Amendment-protected activities. I recommend all chiefs look at the findings reports, and particularly the remedial recommendations, from the DOJ investigations in Phoenix, Louisville, and Minneapolis. See how you can implement those recommendations in your city today. And it can’t be “check the box” reform, because I think we’ve gotten good at changing policies and saying, “Oh, that’s done.” As in the story I told you about my interaction with the Louisville mayor, you need to be able to prove to a skeptic that you’re performing to standard. Wexler: DOJ found that “[the Phoenix Police Department] and the City unlawfully detain, cite, and arrest people experiencing homelessness and unlawfully dispose of their belongings.” What are your thoughts on that finding? Chief Sullivan: I can only speak to what I’ve experienced since I’ve been here, and I haven’t seen evidence of one incident of us disposing of homeless folks’ property. DOJ’s investigation included incidents before I got here, from 2016 to 2022, and we’re certainly not the department we were in 2016. Since I’ve been here, the city and department have led with services. The city has an Office of Homeless Solutions and a Neighborhood Services Department. And the police department supports their efforts.

Source: Instagram Wexler: Can it be challenging to balance the project management skills – implementing the hundreds of stipulations in the agreement – and the leadership skills – motivating your staff as they face public scrutiny? Chief Sullivan: Absolutely. I think we’ve seen cops in cities under oversight from the Department of Justice lose their engagement at times, and then those cities saw a rise in violent crime. Cities need to make sure they keep the cops informed. My city manager, my deputy city manager, and I have been holding a series of sessions to sit down with our folks and discuss where we are as a city in this process. For the last two years, I’ve been telling our staff that the findings report would probably make them feel bad. It would paint an image of a department that they’ve grown up in that doesn’t look like what the vast majority of them have experienced, and it would be a gut punch. I was no longer in Louisville when the police department came under investigation, but I read the findings report, and that’s how it felt to me. The day the findings report dropped, I started meeting with folks, and they said, “Yeah, that really hurt. It felt like a gut punch.” You need to listen to cops and answer their questions as they go forward, and they have to know you have their best interests at heart as you engage with elected officials and the Department of Justice. You’re managing both the police department’s view and the community’s view, so it’s not an easy job.

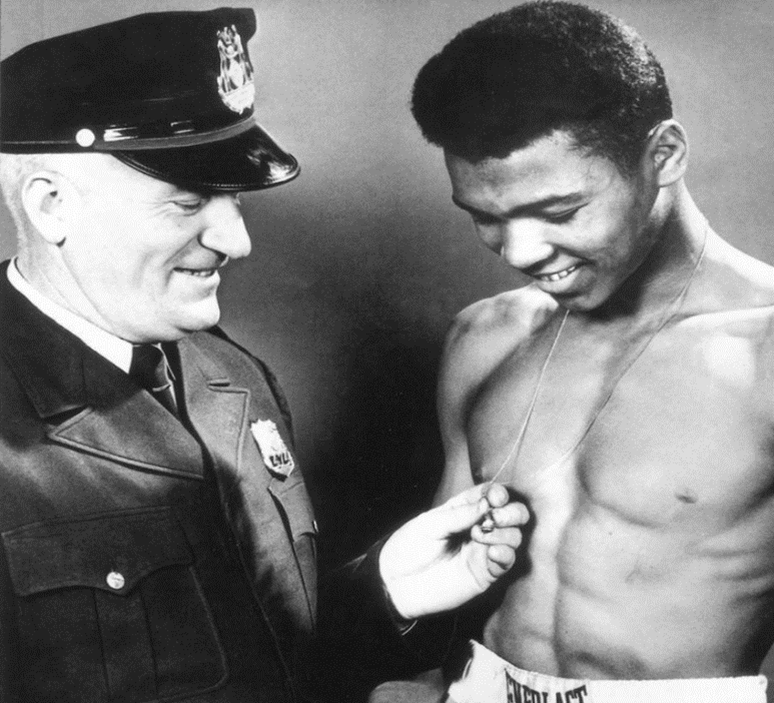

Chief Sullivan attends the annual Michelle Cusseaux Mental Health Fair and Toy Drive to raise awareness for mental health. Source: Instagram Wexler: How do you stay motivated? You’ve been in three challenging departments, but you sound pretty optimistic to me. Chief Sullivan: I think we need to continually recognize the impact we have on communities. Cities can’t thrive unless they have good public safety. Whenever we have a graduation ceremony, I talk about how this job is not about law enforcement; it’s about public safety and providing justice for victims and communities. If you don’t believe in that mission, you probably shouldn’t be in this career. I know I wouldn’t be able to do this job if I didn’t believe in it. That drives me every single day. I was at Muhammad Ali’s funeral, and [his wife] Lonnie Ali told the story about the Louisville police officer who encountered Ali when he was a 12-year-old kid who had his bike stolen and was ready to beat somebody up. The officer told the kid to come to the gym to learn how to box. That connection changed Ali’s life forever. And the chance to lead women and men to go out and do that work every single day inspires me.

Officer Joe Martin and a young Muhammad Ali, formerly Cassius Clay. Source: Courier-Journal/Wikimedia Commons Thanks to Chief Sullivan for taking the time to speak with me and share his wisdom with PERF’s membership. Have a wonderful weekend! Best, Chuck |