|

July 12, 2025 CVI programs have played an essential role in preventing violence for 25 years

PERF members, Community violence intervention (CVI) programs have been around for decades. When these programs were first introduced, I believe many in law enforcement were a bit skeptical. Some programs hired former gang members or other individuals who had previously committed crimes. Chicago’s CeaseFire, which became Cure Violence, began in 2000, and PERF did work in the city around that time and in the years since. I saw firsthand that the trust between police and outreach workers wasn’t built overnight. A police district commander might take incremental steps to share additional information. Sometimes mutual trust developed, and sometimes it didn’t. In recent years, I think police have gained more experience with CVI programs and come to view them more positively. But there has been little research into the role of law enforcement in CVI programs. To help fill that gap, PERF’s research team recently released a publication and accompanying research brief on law enforcement agencies’ role in CVI programs. PERF’s Research Director Dr. Meagan Cahill wrote in a 2022 column that “three evidence-based approaches are considered core CVIs: violence interruption programs, group violence intervention programs, and hospital-based intervention programs.”

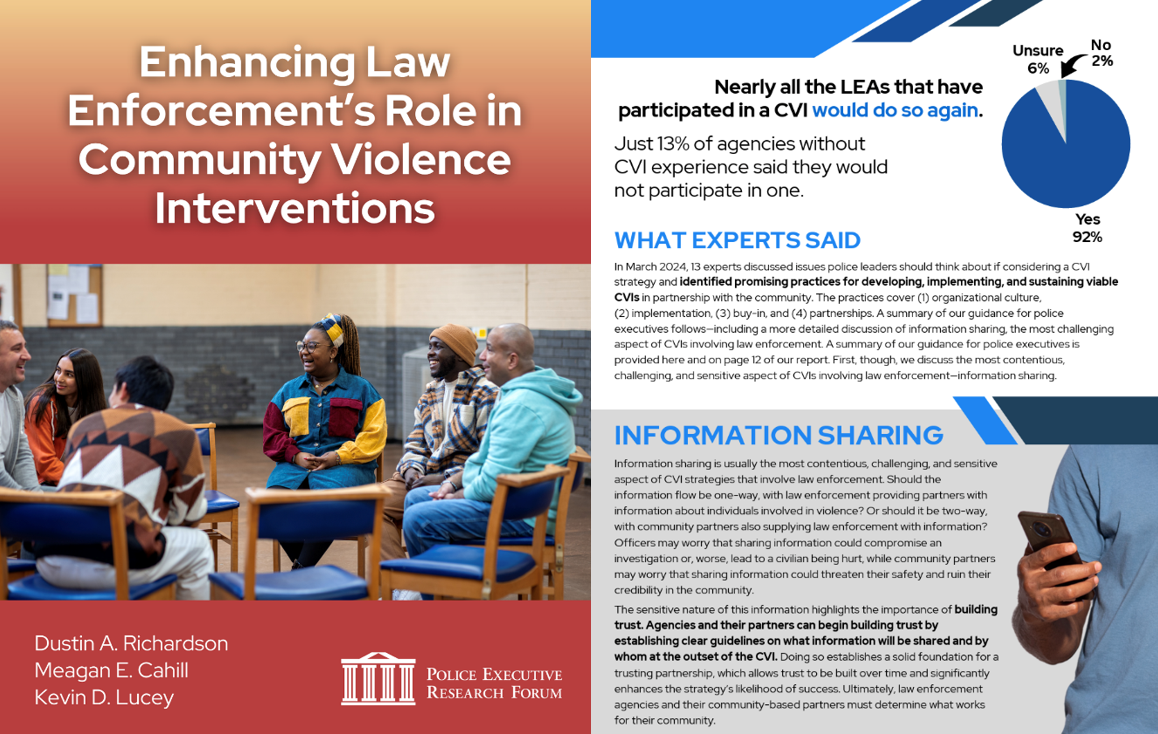

Before I tell you more about the report, I want to share a few comments from police chiefs about CVI programs in their cities. Commissioner Kevin Bethel, Philadelphia Police Department: We have a group violence intervention team that comes under the Office of Safe Neighborhoods for the city. To give you a quick history, I was very much involved in focused deterrence, which was a very hard strategy on trigger-pullers and was highly effective in our work but never really had a community-based component to it. We would not be able to maintain that strategy over a period of time. By the time I left in 2016, that was kind of going away. In 2020, they brought in a group violence intervention. That is going phenomenally well. When I came back [in 2024], they had a very good strategy. They had a lot of folks on the ground to be able to deal with retaliation. It was much more community-based—how to provide supports and give them direction and jobs. It was the stuff that was missing from the original model. Those things were promised but never fully realized. We just had a big mass shooting, and the first group we called up was our group violence intervention team to get them on the ground to see what’s going on. Every week we host a shooting meeting where we look at areas where we’re having violence. We pinpoint individuals we want them to contact. They give me weekly reports about whether they’ve made contact and provided services. I never thought we’d be here with the relationship, but [Director of Group Violence Intervention] Deion Sumpter is an exceptional young man who has built a great rapport with the police department. So we’ve come to rely heavily on them for getting on the ground, finding out what’s going on, and trying to stop the retaliation. Chief Robert Tracy, St. Louis Metropolitan Police Department: [CVI] is part of our comprehensive plan. We share anonymized crime information about hot spots and incidents where there are shots fired or nonfatal shootings and retaliation could be kicking off. So this is an intelligence-sharing operation, and you have to build trust without us giving up investigations or them losing their street credibility. We’re working alongside one another for the best outcomes possible, where we’re arresting the perpetrators causing the crime and, at the same time, trying to slow down the retaliation. So I feel they’re really important when they’re used properly. In St. Louis we’re working with an Office of Violence Prevention. It has a lot of other components, like focused deterrence. But these violence interrupters, who have the relationships in the streets and may have criminal histories, have legitimacy. I think being able to trust them and work together with them gives us the best chance for success. Commissioner Richard Worley, Baltimore Police Department: Our biggest [CVI] partner is Roca. They’ve been here several years, and over the last couple years they’ve really amped up and been a great deal of help for us with young men. As part of our focused deterrence model—which is a partnership with the police, the state’s attorney’s office, and the mayor’s office—we do scorecards to see who is most at risk. We give them a custom notification letter telling them, “If you don’t put the guns down, we are going to come after you with an investigation. You can take services,” and we offer multiple services through Roca. All that is run through the Mayor’s Office of Neighborhood Safety and Engagement. Roca gets all the information about all our shooting victims, and they try to target the most at-risk individuals to get them out of the game. One thing that probably helps them a great deal is that they are persistent. If someone tells them “no” three or four times, they’re going to keep trying to get the young person on board. Then they work with them to get them education, jobs, relocation, or anything that can help them. PERF surveyed its membership for our new report to better understand police participation in CVIs. More than 200 agencies responded to our survey; the vast majority of respondents (85 percent) said they believe the community shares responsibility for addressing violence. And far more respondents preferred supporting a community-led CVI program (50 percent) than leading one themselves (17 percent). Nearly half (49 percent)of respondents reported they had previously participated in a CVI program. Of those respondents, more than 90 percent said they would do so again. We then convened a panel of experts to discuss key considerations for police leaders interested in CVI programs. One of the most important considerations is how information will be shared. This is usually the most contentious, challenging, and sensitive aspect of CVI strategies. As Chief Tracy mentioned, for a CVI to work well, all parties need to trust that intelligence is being shared in a way that respects everyone’s needs. The panel identified the following four key questions leaders should ask themselves before participating in or initiating a CVI program:

If a chief or sheriff thinks their agency may fall short in any of those areas, the report includes recommendations for improvement. This report is particularly timely because of the recent funding cuts to U.S. Department of Justice grants. According to the Council on Criminal Justice, nearly $170 million in funding for community safety and violence reduction programs was eliminated. I hope the current presidential administration recognizes—as many police chiefs and sheriffs have—that CVI programs can help prevent violence. I appreciate all the hard work CVI workers do to prevent violence in their communities. CVI workers take risks and, at times, have been victims of violence themselves. For example, three outreach workers were killed in Baltimore from January 2021 to January 2022. Thanks to Research Director Meagan Cahill, Senior Research Associate Dustin Richardson, and former Senior Research Assistant Kevin Lucey for leading this project, and I’m grateful to the Joyce Foundation for supporting this important work. Best, Chuck |