|

Critical incidents can be dynamic and dangerous. First Line Supervisors (FLSs) can benefit from having resources to help them manage these situations. This section contains several strategies for effectively managing a critical incident including PERF’s Critical Decision-Making Model, the 7-C’s of a Critical Incident, a checklist for managing a critical incident, and additional resources provided by several other law enforcement agencies

PERF’s Critical Decision-Making Model (CDM)

Background information on the CDM Background information on the CDM

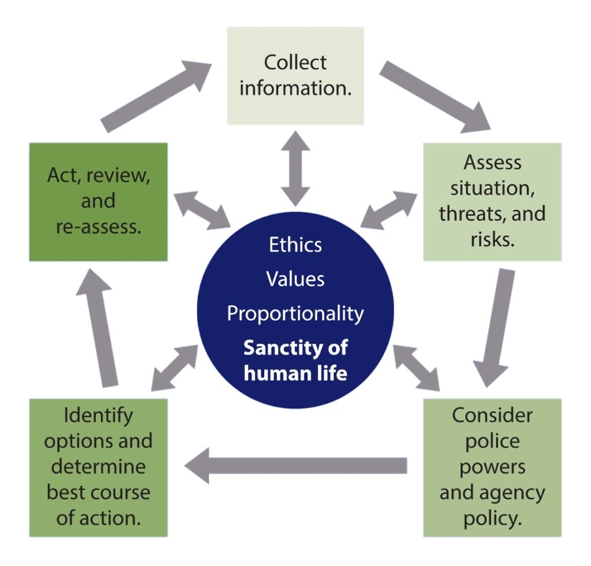

Adapted from the police forces in the United Kingdom, PERF’s Critical Decision-Making Model (CDM) can help law enforcement personnel quickly make organized, logical, and ethical decisions. PERF has primarily used the CDM as a decision-making tool when training agencies to de-escalate potential use-of-force incidents; however, the CDM can be used by law enforcement as a decision-making tool for many types of critical incidents.

The CDM is a five-step tool that is anchored by a set of core values (customized for each agency). The CDM can help first-line supervisors (FLSs) make crucial and time-sensitive decisions during critical incidents. When supervisors work their way through the CDM, or “spin the model,” they will go through a structured set of directions that will help them manage dynamic situations and ensure a safe outcome.

If the issue is not resolved, FLSs must go back to Step 1 and continue the process by beginning to collect more information. As information evolves, supervisors should reevaluate the response, change and reallocate resources, and update all responders on the new direction of the operation. This process is called “spinning the model.” FLSs should “spin the model,” considering each step of the CDM until each issue is successfully completed and the critical incident is resolved.

At each step in the model, FLSs should be considering the CDM core to determine whether each action taken is in accordance with their agency’s mission and values. This helps to ensure that all decisions made and actions taken are in accordance with department policy and the critical incident is resolved safely.

The CDM provides a structure for how many law enforcement officials, supervisors, and officers already make decisions. Like any new activity, the CDM becomes second-nature with enough practice.

Core Core

The CDM is a circular five-step process that first-line supervisors can use to safely and efficiently resolve critical incidents. In the middle of the CDM is the core. PERF recommends that departments and individuals edit the core and enter the principles that guide all of their work. Ethics, values, proportionality, and the sanctity of human life are important factors when considering any decision; however, other principles may be more important for agencies when they consider this decision-making processes.

- Step 1 – Collect Information

Collect all information possible prior to arriving on scene. This includes listening to radio transmissions by dispatchers and officers, scanning call information on a mobile data terminal, and reviewing prior calls for service at the location of the incident or criminal history of any of the involved subjects. While it is listed as Step 1 in the CDM, information collection is an ongoing activity when using the model.

- Step 2 – Assess the situation, threats, and risks

Supervisors gauge the magnitude of the critical incident and assess factors such as whether the initial information is accurate, if there are enough personnel on scene, whether immediate police action needs to be taken, and if there are any risks present to officers or bystanders.

- Step 3 – Consider police powers and agency policy

While it may be a given on critical incident scenes, supervisors should always determine whether their officers have the legal right to be on scene. FLSs should ask themselves if this is a police matter, and, if so, given the information the FLS has collected and assessed, what are the legal powers they have and how do their agency’s policies guide their decision making?

- Step 4 – Identify options and determine the best course of action.

This step includes:

- Considering what you are trying to achieve during the critical incident:

- Address immediate threat.

- Take the subject into custody. Note that in some instances taking the subject into custody right away might not be advisable or necessary.

- Establish communications with the subject (if possible).

- Attempt to buy more time for additional officers or resources to respond to the scene.

- Communicating with their officers.

- Determining the most appropriate tactics to safely and effectively respond to the critical incident.

- Step 5 – Act, review, and re-assess.

In this step, FLSs must act, or give orders to their officers to take action. Once completed, FLSs need to assess whether the actions were completed properly and had the intended effect.

How the Burlington, NC Police Department Uses the CDM

The 7 C’s of a Critical Incident

The 7 C’s were explained to PERF and developed by Inspector Matt Galvin of the New York City Police Department (NYPD). When developed, Inspector Galvin was the Executive Officer of NYPD’s Emergency Services Unit (ESU). The ESU is responsible for responding to many critical incidents in the city such as hostage barricades, suicide-by-cop situations, mass casualty events, and the like. ESU detectives receive additional communications, negotiations, and tactics training. The 7 C’s were explained to PERF and developed by Inspector Matt Galvin of the New York City Police Department (NYPD). When developed, Inspector Galvin was the Executive Officer of NYPD’s Emergency Services Unit (ESU). The ESU is responsible for responding to many critical incidents in the city such as hostage barricades, suicide-by-cop situations, mass casualty events, and the like. ESU detectives receive additional communications, negotiations, and tactics training.

While many of these steps were developed for the NYPD ESU, it is not solely for specialty units like the ESU. Patrol sergeants can master these steps and use this list to be successful on critical incidents. Deploying these tactics and following the checklist can help any group of supervisors and officers to be successful.

C-1. Take Command of the scene.

- There should be a system of roles, responsibilities, and procedures that ensure command of personnel and resources are funneled through one entity.

- Always designate an Incident Commander (IC) regardless of the size and nature of the incident. Sometimes, the IC may be a first-line supervisor, who needs to be prepared to manage and direct officials who outrank the FLS.

- Establish a command post. The command post should be staged in a location a safe distance away from the incident scene.

- In large-scale incidents that may require the response of multiple agencies or jurisdictions, consider unifying the command so all agency commanders can coordinate the incident response.

- Display confidence. When FLSs project confidence, they in turn instill confidence in their officers. No one wants to follow orders from someone who is not confident in their decisions. If an FLS is confident, it will make their officers more decisive and officers will be more likely to follow orders from the FLS.

- Be the supervisor. While this may seem obvious, FLSs need to focus more on the big picture of an incident, gathering intel and delegating the smaller tasks. FLSs cannot operate as both a first responder and a supervisor. This supervisory mindset is different from that of an officer, and some supervisors struggle to make the transition.

C-2. Be in Control

- FLSs must always keep themselves under control during a rapidly evolving, stressful, and emotionally taxing critical incident. There is an “emotional contagion” at work in critical incidents: when FLSs are calm and under control, the people they are directing are more likely to act the same way.

- Being calm during a chaotic situation also helps instill confidence in responding officers. Officers will look for guidance on how to react themselves.

- FLSs must ensure the actions of those under their command are controlled and focused on the mission/task at hand.

- If officers are using excessive force, acting in a way that endangers fellow officers or bystanders, or jeopardizing the police response to the incident, FLSs have a duty to intervene and remove those officers from the incident.

C-3. Communicate

- FLSs must clearly and calmly communicate to their officers and over the radio.

- Clear communication facilitates efficiency and teamwork.

- Communication can help with decision-making. Someone else on scene may have had similar experience and could recommend a best practice approach.

- Always be clear in issuing directions and ensure all officers, not just a few, understand what directions they are to follow. During a chaotic scene, orders can easily be misunderstood. FLSs should speak clearly and directly to their officers, naming them when giving commands. For example, FLSs could say:

- “Officer [Name], watch that door.”

- “Officer [Name], stand by this evidence/weapon.”

- “Officer [Name], go with the ambulance to the hospital.”

- Ensure that there is a common radio channel at an incident. That radio channel must be kept clear of non-incident communication. If not, it can lead to agencies or individuals not knowing or understanding what actions are being conducted.

- As the incident commander, the FLS is also responsible for communicating updates to agency leaders, command centers, etc.

C-4. Containment – make sure the scene is safe.

- Establish perimeters and zones (hot/warm/cold).

- Control ingress and egress points.

- Consider the possibility of a sudden and unexpected event that occurs at an incident and how to respond without overwhelming or overtaking the overall mission.

C-5. Coordinate the resources that are available to you.

- No critical incidents are static. There will always be moving parts.

- Coordination ties together the prior four C’s. This ensures a safe and efficient incident response.

- Preventing unnecessary personnel from entering and operating within the scene. At many critical incidents, there is a tendency for personnel to “self-dispatch” to the scene. The incident commander should be clear with dispatchers on what resources are—and are not—needed on the scene.

- Those officers and resources that respond to the scene should report to a previously established staging area.

- Have situational awareness to quickly determine where to direct responding officers and resources.

- Be aware of your officers’ strengths and weaknesses; know what resources your agency has and know how to call for them; and be familiar with the area to plan for the best response.

- Officers’ biological needs should be considered, including food and water as well as bathroom breaks. Consider partnering with outside organizations such as the Red Cross or Salvation Army for assistance.

C-6. Complacency – these incidents are dynamic; do not become complacent.

- FLSs must ensure they and their officers do not become complacent, especially during long operational periods.

- Complacency can occur at all ranks on scene.

- Maintain situational awareness.

- FLSs should consider adequate relief and rotation to refresh personnel if possible.

C-7. Critique – Conduct debrief sessions to discuss both positive and negative actions during the incident. (This “C” is covered in greater detail in Part 3 – After a Critical Incident.)

- Debrief sessions ensure that mistakes aren’t repeated at future incidents.

- Use debrief sessions as a learning opportunity to train and prepare for the next incident.

- Use constructive criticism.

- All primary personnel on scene have a perspective and should contribute to the discussion.

- Identify vulnerabilities, pitfalls, and shortcomings.

The 7-C's in Practice – An Example from the NYPD

Checklist for Managing Critical Incident Responses

Below is a checklist that agency first-line supervisors (FLSs) can use in managing critical incidents. Agencies and supervisors should consult both best practices and their agencies’ policies before constructing a comprehensive “checklist” that provides detailed, concrete steps that FLSs should take in key areas. The following checklist can be used as a guide. Below is a checklist that agency first-line supervisors (FLSs) can use in managing critical incidents. Agencies and supervisors should consult both best practices and their agencies’ policies before constructing a comprehensive “checklist” that provides detailed, concrete steps that FLSs should take in key areas. The following checklist can be used as a guide.

- Establish a perimeter and isolate the subject or the focus of the incident.

- Secure the scene and, if necessary, evacuate civilians.

- Establish a command post and staging areas a safe distance away from the scene for officers and resources to respond to.

- Manage and assign personnel responding to the scene. Assignments could include:

- Managing traffic

- Maintaining a perimeter

- Responsibility for making notifications

- Hospital or prisoner transport

- Information control or scene scribe

- Evidence/weapons control

- Plain clothes or field intelligence to talk and listen to civilians

- Canvass the area for suspects, victims, and/or witnesses

- Manage self-deployments

- Ensure that self-deployed officers do not overwhelm an already chaotic scene.

- Ensure enough officers remain in service to handle the normal calls-for-service not related to the critical incident.

- Traffic management (including maintaining points of entry for arriving resources)

- On the perimeter, ensure that there are clear access and exit points for other first responders, such as the fire department and EMS.

- Inside the perimeter, there should also be a route cleared for emergency vehicles to access the location in the event that victims need to be transported to the hospital or other time-sensitive actions are required. Responding units should only park on one side of the road to leave room for these vehicles.

- Internal communications

- Make all notifications to senior officials and department entities.

- If possible, have another FLS or assign an officer to maintain communications with senior officials who may ask for updates during an incident.

- Ensure that the dispatch center is kept informed of all major developments.

- Keep officers informed of major developments on scene

- Solicit information from senior officers and the first officers to arrive on scene.

- If possible, have all participating units switch radio channels or work with dispatch to keep the radio clear of non-critical incident communications to ensure that participating units can communicate clearly and effectively during the incident.

- External communications

- Ensure that witnesses and anyone associated with the subject (if applicable) are interviewed.

- If unfamiliar with a building’s layout, solicit information from people who work or reside in the building (if applicable).

- When possible, communicate pertinent public safety information with the civilians directly impacted by the critical incident.

- Establish a designated media area and assign a PIO or supervisor to give updates.

- Warm handoff

- If an incident extends into another shift, ensure all relevant information is shared with any personnel relieving the outgoing shift, especially other supervisors.

- Documentation

- If possible, assign a scribe to record all personnel arriving and leaving the scene of the critical incident. The scribe should also document all resources that arrive on scene and major actions taken. Scribes should also record the times for all major actions.

- Dry erase whiteboards should be used by the incident commander. All intelligence information, scene diagrams, officer assignments, and operational directives, can be illustrated on the boards. The whiteboard allows for smoother transition of command and can be photographed as evidence for after-action reports.

Here are examples of critical incident checklists being used by some agencies. If you would like to have your checklist added to this list, please contact PERF.

Helpful Resources:

This project was supported, in whole or in part, by cooperative agreement number 2018CKWXK016 awarded to the Police Executive Research Forum by the U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Community Oriented Policing Services. The opinions contained herein are those of the author(s) or contributor(s) and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

|

Background information on the CDM

Background information on the CDM

The 7 C’s were explained to PERF and developed by Inspector Matt Galvin of the New York City Police Department (NYPD). When developed, Inspector Galvin was the Executive Officer of NYPD’s Emergency Services Unit (ESU). The ESU is responsible for responding to many critical incidents in the city such as hostage barricades, suicide-by-cop situations, mass casualty events, and the like. ESU detectives receive additional communications, negotiations, and tactics training.

The 7 C’s were explained to PERF and developed by Inspector Matt Galvin of the New York City Police Department (NYPD). When developed, Inspector Galvin was the Executive Officer of NYPD’s Emergency Services Unit (ESU). The ESU is responsible for responding to many critical incidents in the city such as hostage barricades, suicide-by-cop situations, mass casualty events, and the like. ESU detectives receive additional communications, negotiations, and tactics training.  Below is a checklist that agency first-line supervisors (FLSs) can use in managing critical incidents. Agencies and supervisors should consult both best practices and their agencies’ policies before constructing a comprehensive “checklist” that provides detailed, concrete steps that FLSs should take in key areas. The following checklist can be used as a guide.

Below is a checklist that agency first-line supervisors (FLSs) can use in managing critical incidents. Agencies and supervisors should consult both best practices and their agencies’ policies before constructing a comprehensive “checklist” that provides detailed, concrete steps that FLSs should take in key areas. The following checklist can be used as a guide.

![Go to the Helpful Resources section Helpful Resources [section header]](/assets/images/CRTimages/helpfulresources_sh.jpg)